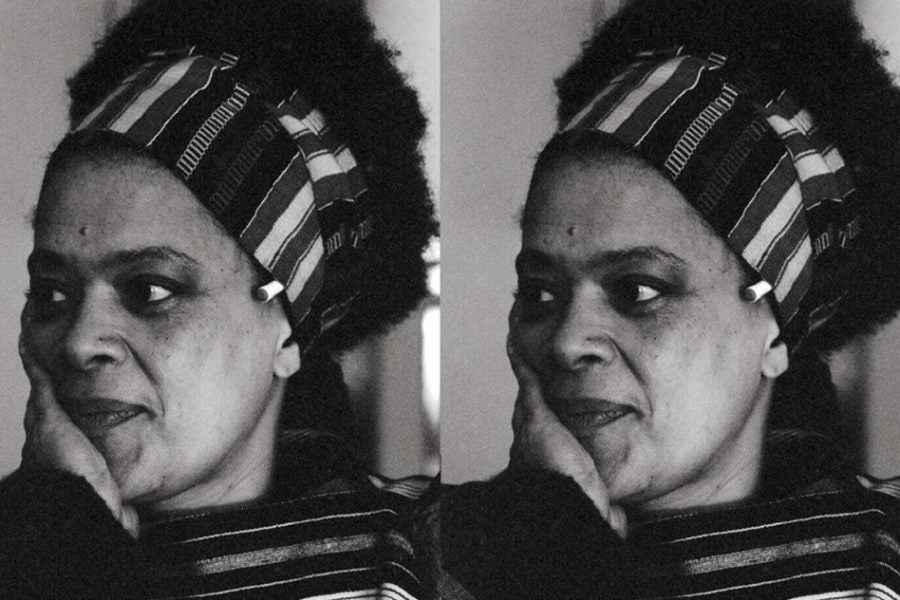

Peniel E. Joseph wears many “hats”—he is a professor, the founding director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy (CRSD) at the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin, and he serves as the Associate Dean for Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion. In addition, Joseph is a prolific and award-winning author, with the majority of his career spent focusing on “Black Power Studies,” which covers an array of “interdisciplinary fields such as Africana studies, law and society, women’s and ethnic studies, and political science.”

Joseph’s latest book (out September 6, 2022) is entitled “The Third Reconstruction: How a Moral Movement is Overcoming the Politics of Division and Fear,” and has already received rave reviews, including being named a Top Ten History Title for the Fall by Publishers Weekly.

“The Third Reconstruction” concentrates on the period between the historic presidential election of Barack Obama in 2008 and the insurrection at the Capitol on January 6, 2021, an era which Joseph has coined our nation’s Third Reconstruction, and his book spotlights the threads and commonalities which have connected this time with the prior two reconstructions in U.S. history.

Providing a unique perspective, this book is part historical narrative, partly critique of culture, and part quasi-memoir. In Joseph’s words, he is “hugely excited about our folks…especially, Black women [reading the book], it’s really dedicated to them and their work, and this is the first book where I had a real chance to get into that [Black feminism] space in a big way.”

Recently, Joseph spoke with ESSENCE about why he felt compelled to write this book now, the importance of Black women to the movement, and his hope for the future of our country.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

ESSENCE: What was your initial inspiration for writing the book?

I’ve always been interested in the period of reconstruction, even though I’m a technically a late 19th century and 20th century historian. I think the election of Trump in 2016 really made me drill down. So even before 2020, it was really the shock of 2016 after Obama, because I was one of the people who was very supportive of the president and was thinking that this meant something really transformative in a very positive way for the country, but definitely for Black people, and I wouldn’t have thought that the end of that rainbow was Donald Trump.

ESSENCE: I’ve heard of the first Reconstruction before, but your book is entitled “The Third Reconstruction.” What was the second reconstruction?

My late mentor was the first person who coined that term, and in my book, I have it as the high point of 1954 to 1968. Technically, you could go a decade earlier and say it starts during the Second World War, and you could also say that it continues into the early- and mid-1970s. When you think about the rise of the Congressional Black Caucus, Shirley Chisholm, Barbara Jordan, the 1976 Democratic National Convention, and the Watergate hearings, the second reconstruction is really trying to make up for the shortcomings and the failures of the first and that’s why you see this laser-like focus on both voting rights and desegregation. Those are the two pivot points, and during this third [reconstruction], this is where you’ve really gotten more into what parallels the first: redistributive justice, people thinking more about wealth and wealth creation, not just income and employment, but also reparations.

ESSENCE: Why do you think this book is so necessary right now?

It provides us a context to explain the events of not just 2020, but why we keep getting these recurring patterns, and also what’s distinctive about this period, and especially throughout the book, I look at Black women and Black women’s centrality to the story. It provides an important context in terms of transforming the narrative and what stories we tell ourselves actually encompass American history and who are the central actors in both stories. It’s a story that everyone should know, but especially Black folks.

It’s about the theme of reconstructionist versus redemptionist because I think one of the through lines of the book is this idea that, irrespective of color, there are people who are reconstructionist, who are believers in multiracial democracy, and I highlight Black women who have been reconstructionist. Redemptionists are advocates of white supremacy, irrespective of race, class, gender, sexuality.

Part of it is making people understand that battle or conflict between reconstructionists and redemptionists did not end after the Civil War, after reconstruction. It continues to animate both political parties. It’s what led to political realignment. It’s what led to certain historical contexts. It’s important for us to understand that we are constantly in that struggle between reconstructionists and redemptionists, and if we want a more just future, we’re going to have to embrace that reconstructionist future. It’s something I’d like people to wrestle with and take note of– where do they see those reconstructionist and redemptionist impulses in their own lives and their own politics today?

ESSENCE: You’ve mentioned that history continues to repeat itself in a circular fashion. Are you hopeful that things are going to change for the better and not continue in this vicious cycle?

When we think about Martin Luther King, Jr., and Selma or Birmingham, the March on Washington and the Voting Rights Act, the outcomes that we remember, that we celebrate, were not predestined outcomes. We literally made that happen, and we’ve had victories and defeats. Part of my hope is that people understand that we actively shape this history, even though there are forces that are trying to make sure that the outcome manifests itself in one way, you can still resist that. I think that’s important to know because you feel more empowered if you know that you can impact what’s happening in your neighborhood, school, city, state, country, rather than thinking that no matter what you do, the outcome is preordained. We can create a different story and a different outcome.

“Black women were equal architects of the liberation struggle and liberation movement.”

ESSENCE: Why do you think the roles of Black woman have been so often overlooked during the first, second and third reconstructions?

I think it’s the patriarchy, it’s racism and sexism, propelled by the myth of the able-bodied Black man who is going to help us out of this when in reality, Black women were equal architects of the liberation struggle and liberation movement. I would say that during the third, it’s been less overlooked, and people have been more willing to acknowledge that even though we don’t have equity and parity yet. That’s why I singled out people like Angela Davis, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Stacey Abrams, Kathy Cohen, Beth Richie, and Audrey Lorde, and so many other people who’ve been doing the work, in my book.

ESSENCE: You were raised by a single mother. Can you tell me more about how your background has impacted your experiences, and specifically your lens of interpretation during the period of the third reconstruction?

My mom is an immigrant from Haiti who came to United States in 1965 to New York City. I was born and raised during the 1980s in Brooklyn and Queens, and my mother’s impact and influence was really indelible. She was my first history teacher and is the person who taught me about social justice. She was part of a hospital workers union, SEIU 1199 at Mount Sinai Hospital, so I was on my first picket line in elementary school, and I really learned about the history of Black women, both in Haiti and the United States. So, I got a huge interest, not just in history, but Black feminism, which became one of my areas of expertise and study at Temple University. My mom is hugely crucial to all of this because she was somebody who was guiding me every step of the way, so she’s been my biggest role model in that sense.

ESSENCE: What do you hope is your readers’ biggest takeaway?

I hope they feel empowered by the knowledge of this history and impressed by all the Black people this book highlights, especially the Black women who’ve done so much to try to transform American democracy for all people, particularly Black people. I hope they feel hopeful and get invigorated and inspired to continue to do the work. We can forge that new story ourselves, so there is still hope, simply because of Black people’s determination and resilience and belief that we can build a different kind of democracy.