When Columbia Records announced that they had signed their first-ever AI Hip Hop artist in mid-August, it seemed like the natural next step in the industry’s integration into the Metaverse. Completely generated both visually and sonically by programming algorithms, FN Meka was seemingly primed for superstardom in both the physical world and the internet’s third generation.

But it quickly came crumbling down when fans got an eyeful of their newest artificial Hip-Hop freshman – green locs, face tattoos, vaguely multi-ethnic features – and even worse when they got an earful of his slur-laden lyrics, proudly describing a lifestyle of crime and struggle he had never lived, particularly since he was technically imaginary.

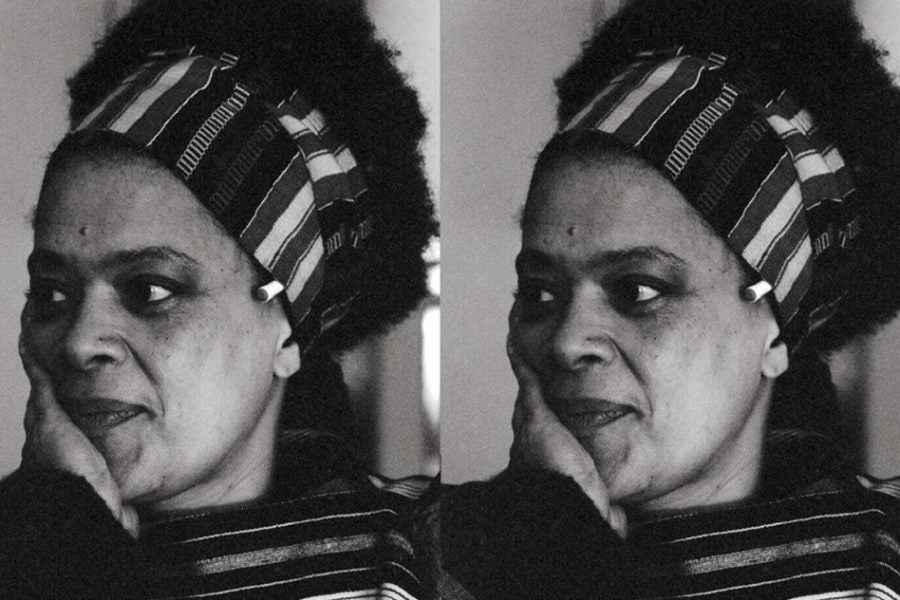

“I think the overarching misstep here is that FN Meka is supposed to represent a caricature from Black culture,” says Sinead Bovell, futurist and founder of WAYE, a tech education foundation. “But the people benefiting off of this identity and the people controlling this identity aren’t from the Black community. And this opens up lanes for exploitation to occur.”

FN Meka is the brainchild of Brandon Le and Anthony Martini, co-founders of Factory New, a tech organization specializing in the creation of virtual identities. As Martini told Music Business World in April 2021, beyond the rapper’s visual image, everything about him was analyzed from already popular rap songs and generated through computer analysis, from the beats he flowed over to the lyrics he spat.

FN Meka is far from the first AI musical artist, as many exist in the marketplace across other genres. Hatsune Miku, K/DA, and Miquela Sousa each have bonafide hits and fans in the Pop genre. However, once you dip into Hip Hop, a genre that was forged in the struggle of marginalized Black and Brown people, there is a whole other set of complications to contend with when you’re creating a figure out of thin air. Not to mention that FN Meka’s entire being is an amalgamation of existing sounds and imagery that real living Black people have popularized.

“When people aren’t in charge of their own stories, or you don’t have somebody from the identity speaking about their own identity, there’s a massive opportunity for stereotyping and appropriating to occur,” Bovell explains. “And that’s what I think has happened here.”

“Hip Hop is largely based on sociopolitical and historical experiences. It’s a response to racial inequalities. And so, AI and avatars, they present this opportunity to instead commodify these historical experiences, and these responses to inequalities, reduce it down to packets of data, then sell it back to the communities these virtual artists are supposed to be speaking about and speaking to.”

After releasing a new single entitled “Florida Water,” featuring Gunna and DJ Drama, to public outcry and balks of digital Blackface – particularly notable was activist nonprofit Industry Blackout’s open letter calling the AI figure out as “a direct insult to the Black community and our culture” – Columbia quickly dropped the project, issuing a statement of apology.

“We offer our deepest apologies to the Black community for our insensitivity in signing this project without asking enough questions about equity and the creative process behind it. We thank those who have reached out to us with constructive feedback in the past couple of days — your input was invaluable as we came to the decision to end our association with the project.”

But as Bovell notes, the entire PR fiasco was avoidable, if the label had only stopped to consider the sociodemographic implications of their newest foray into tech.

“You also have to consider, with technology, how it intersects with factors like race, gender, sexual orientation. What the music industry is now experiencing is that it too is becoming part of the tech industry, as every industry is, which means you have to consider the ethical challenges that accompany those tools.”

The use of AI in the industry, even beyond virtual figures, may not be a new advent, but cases like FN Meka are causing consumers to wonder what this new future, where computers run the show, may look and sound like for listeners.

“Why this spot feels a little bit more of an intimate change is that the final point in the supply chain that consumers engage with, the artists themselves, is becoming digitized, and that feels really strange.”

But Bovell wants consumers and artists to bear in mind all the good that can come from integrating tech into art, good they are likely already enjoying the product of, and what that could mean when put to use ethically.

“On the good side, this type of tech can empower creators. So if you are an emerging artist and you are a great lyricist, but maybe you’re not a great singer or performer. AI could step in here, for instance.

“I hope that this can be a wake-up call,” Bovell said. “This is a big learning experience for companies, for artists, for the future.”