Sepsis is one of many health challenges we can encounter as humans, but perhaps one we don’t speak about enough. At a minimum, 1.7 million American adults get sepsis yearly, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Children are especially vulnerable to the condition—more than 75,000 children in the United States are affected, and it’s the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in little ones globally.

Black children are also more likely to die from sepsis than their white counterparts. We spoke to pediatricians to find out why this is, what sepsis is, and how it’s treated.

What is Sepsis?

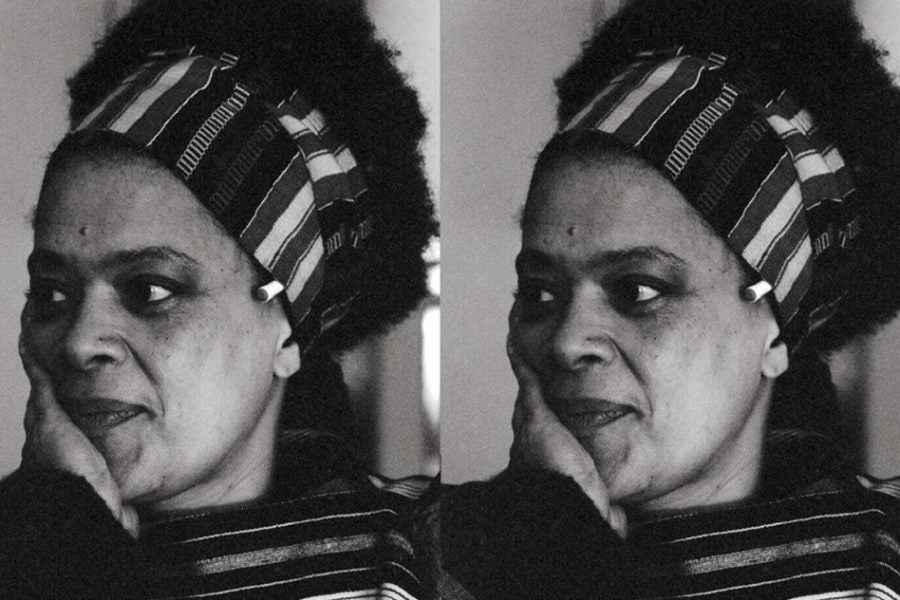

When you get an infection, your body works hard to help you recover. When your body has an extremely inflammatory response to an infection, this is known as sepsis, Dr. Angela Holliday-Bell, a pediatrician and certified clinical sleep specialist in Chicago, Illinois.

“Usually that’s gonna be bacterial, but it could be viral, it could be fungal, but it’s a cascade of processes and reactions that take place in your body as a response to some sort of infection,” she tells ESSENCE.

This infection can be life-threatening, and there are different stages to the condition. There is sepsis and also severe sepsis. “When you get to that point, there’s evidence of some end-organ damage, meaning one of the organs [are] not functioning properly,” says Holliday-Bell. Severe sepsis can also lead to septic shock–the last stage of sepsis–when an individual’s blood pressure becomes dangerously low despite IV fluids.

Signs, Symptoms, and Treatment of Sepsis

Sepsis symptoms can be so general that it’s hard to tell if something serious is going on, especially in children who can’t communicate yet.

Some signs and symptoms include high heart rates, a weak pulse, fever, shortness of breath, sweaty skin, or extreme pain and discomfort.

You may not spot some of these symptoms in your child immediately, especially ones such as a high heart rate, says Holliday-Bell.

“It’s hard for a parent; they’re not necessarily gonna take a respiratory rate or a heart rate if [their] child is not acting like themselves,” Holliday-Bell says.

“If they look at them and they seem to be breathing quicker than normal, or they are listless and not active, not hydrating, all those things could be signs that there is something more serious going on to your standard cold or infection and is a reason to seek care either from their primary provider or an emergency room.”

It’s crucial you look out for these symptoms and take them seriously if you notice them in your child. If not, their condition could advance to a severe case of sepsis, which can be deadly.

In diagnosing sepsis, there isn’t a single test healthcare providers use. They could use a combination of blood and urine tests, ultrasounds, spinal fluid tests, x-rays, and tests for inflammation or bacterial infections. Sepsis is often treated with intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and other medications.

Some people are more likely to get sepsis than others, typically individuals with weaker immune systems. Children under one, people with chronic health conditions, and adults 65 plus are more susceptible.

Why Disparities Among Black Children Persist

The number of sepsis-related deaths among U.S. children has declined over the past 20 years, says Yolanda Hancock, Medical Director of CRC Health & Wellness Group and the Founder of Delta Health & Wellness Consulting in Upper Marlboro, Maryland. Unfortunately, children of color, particularly Black children, don’t account for much of this decline.

A 2020 study published by The Lancet Child and Adolescent Health found Black children had a 19% higher risk of sepsis-related death than white children. Black children also had longer hospital stays–an average of 10 days–versus white children, who averaged eight days.

There are several reasons these disparities exist, and access to care is one, says Hancock.

“Delays in being seen, diagnosed, and treated result in Black children disproportionately losing their lives to sepsis,” she says.

Hancock says that pediatric hospital wards and intensive care units have either significantly reduced capacity or completely closed across the country.

That is bolstered by a 2021 study in the journal Pediatrics that found from 2008 to 2018; pediatric inpatient units fell 19%. This has meant several families have to travel long distances to find care for their children, especially for rural families and communities of color, says Hancock.

She also explains that the pandemic exacerbated this issue as it caused institutions to forfeit pediatric beds for adult care, especially as the latter is more lucrative. A staff shortage also means there may not be enough pediatric doctors to identify a child experiencing sepsis adequately.

Another reason for the disparities is providers’ inability to notice sepsis symptoms in Black children compared to other children. This can be a result of internal biases, says Holliday-Bell. Racial biases, in particular, may be cultural barriers, lack of access to health insurance coverage, or healthcare treatment.

“There are internal biases about how individuals of bigger races respond to let’s say pain or infection.They’re less likely to believe that a child of minority race is having the symptoms that they’re displaying,” Holliday-Bell tells ESSENCE.

Advocating For Your Child

If you suspect your child has sepsis and you’re a person of color, you may have another battle ahead of you when you seek health. As mentioned above, it’s possible you could experience internal biases or find your concerns aren’t taken seriously. This may be a good time to advocate for your child.

You can do this by escalating your concerns and being persistent about it.

“If a parent feels that their concerns are being dismissed, they should ask to speak with the healthcare provider in charge of the emergency department, hospital ward, or intensive care unit to ask why further workup isn’t being done,” says Hancock.

This can be difficult for people of color, especially if they already feel stigmatized for being ‘difficult’ or problematic. Although understandable because sepsis can progress rapidly, it’s not something you want to sit on the fence about. Also, remember that healthcare providers are there to help you, so asking questions and following up isn’t something to be afraid of, says Holliday-Bell.

“Don’t be afraid to ask questions because that’s how you learn, and that’s how you have the knowledge you need to handle situations that may be more dangerous in the future.”