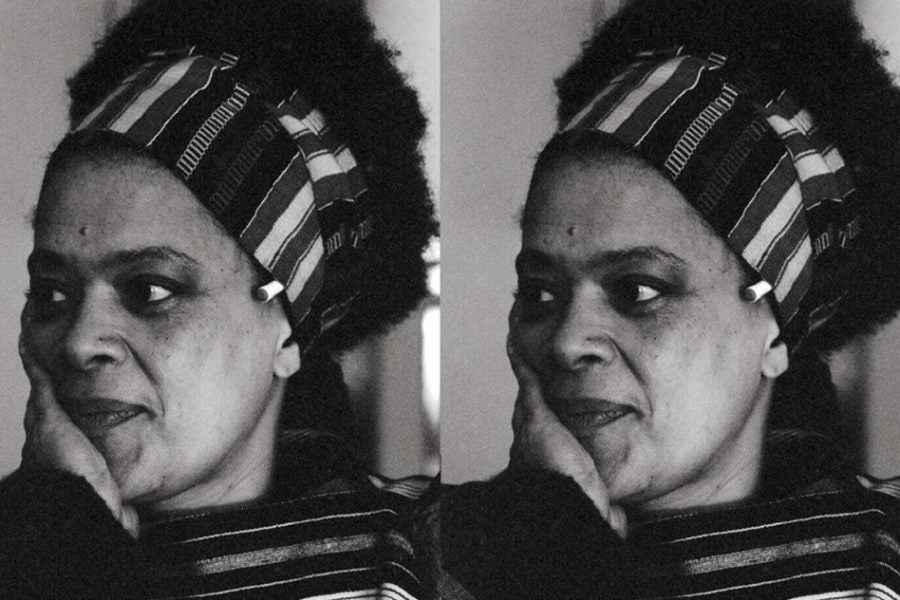

Toni Cade Bambara wore many hats: documentary filmmaker, cultural worker, mentor, educator, mother, organizer and of course, writer. She dedicated her life to Black feminist world making, imagining spaces of freedom and equitable concern. Perhaps most crucially, what Bambara warned us of what we lose when we ascribe to white, patriarchal sex/gender roles.

The revolutionary function of Bambara’s work and its abolishment of sex/gender roles is first fully realized in the storytelling found in Gorilla, My Love, which turned 50 this year. Composed of 15 short stories, Gorilla, My Love comments on the dynamism of familial, romantic, platonic love, untethering love from sex/gender roles. For instance, the story “My Man Bovanne” deals with ageism and ableism, using the budding relationship between Miss Hazel and Bovanne to imagine what could might come from loosening the reins as a mother. To become a “bitch in heat,” a “hussy;” what could change if “‘[we] wasn’t shame.’”

In a conversation for Women’s Studies Quarterly, Hortense Spillers notes how Black culture of the twentieth century followed “a kind of democratic form… It just seemed that that community automatically did something in relationship to being human that was really quite different. That people did whatever work was to be done, whether it was ‘men’s work’ or ‘women’s work,’ if it needed to be done, people simply did it; to raise children, to maintain communities.” The aftermath of this rigid binary has animated Black intramurality.

Discussions on Black life have been hijacked by white heteropatriarchal thinking. It stipulates the following: Black “men” and Black “women” (all while ignoring the personhood of Black queer and trans people) should hate each other because they fail to fulfill all too familiar gender roles.

Bambara’s message, which anchored works like Gorilla, My Love, is made most explicit in her essay “On the Issue of Roles.” Appearing in her 1970 edited collection, The Black Woman: An Anthology, the essay takes a stringent position: an opposition to “the stereotypic definitions of masculine and feminine.’” This position reverberates through Bambara’s oeuvre.

The Seabirds Are Still Alive, which was inspired by a trip Bambara made to Vietnam in 1975, paints the varying intimacies and relations amongst Black folk, amplifying Bambara’s call to measure Black life in relation to “[our] connection to the Struggle,” not by how we fulfill or fail at the roles of “man” and “woman.” Characters like Sweet Pea in the short story “Medley” from The Seabirds, rejects the role of doting partner and narrates the ebb and flow of partnership; long, tender showers filled with song, meet piled up dirty dishes and half-proposals. She reminds us of the lies we need to tell ourselves to fulfill these roles: “I wouldn’t want to be no man. Must be hard on the heart always having to get out there, setting yourself up to be possibly shot down…I don’t think I could handle it myself unless everybody was just straight up at all times from day one till the end.”

In The Salt Eaters (which won an American Book Award in 1981), the novel’s protagonist, Minnie, is an unmarried middle-aged woman, who addresses the mental health crises of folk in her community. She does healing work with Velma Henry, a community activist who suffers from a nervous breakdown from laboring as a Black radical and tries to take her own life. Minnie and Velma defy the gender/sexual thinking that insists Black women contort to the roles of damsels in distress. They instead become the sources of their own self-regard.

Bambara’s description of the use and limits of sex/gender roles resounds loudly in our current moment. It manifests through the platforming of uncritical, reactionary, counterrevolutionary Black voices, that have sided with heteropatriarchy and insists that the roles of “man” and “woman” are the only way forward. We also see it in the public attack of Black people who are not the perceived benefactors of patriarchy: Black people who are not cis, heterosexual Black men. Additionally, the public attack of Black folk who refuse these sex roles and encourage others to defy these roles. For example, the pervasive idea that submission to sex/gender roles “neutralizes the acidic tension that exists between Black men and Black women,” ultimately framing Black people who say “no” to said roles as the source of Black men’s “emasculation.”

Against Bambara’s warning, we’ve made being a “man” or “woman” more important than shared, collective thinking and action not rooted in “male” or “female” thinking. What could be possible if we related around how we can help each other survive this death machine and work towards its undoing? What happens when we forfeit Black culture—not what we simply make (art, music, food, vernaculars, etc.), but how we live, and rage against, in anti-Black world—to assimilate to an anti-Black world that we think we can get a leg up in, if we simply play our roles accordingly?

We carry incalculable hurt, and it is because of this world and our complicity in it; for thinking that if we assimilate to the death contraptions that are sex/gender/sexuality “roles,” that we’ll be spared; that we’ll have what we need to survive or maybe even thrive in this world. And many of us have and will reap the wounding for our “failure” to make good on the promise of being the role of a “woman”/“man;” “wife”/“husband,” “son”/“daughter,” “mother”/“father.” This truth hurts, but in 2022 the lash and the whip of white, liberal bourgeoise sensibilities and our aspirations towards these sensibilities has left the poor, trans and queer of us for dead. If not by using violence as a means of getting folk to bend and contort to these roles, surely sheer neglect and apathy. We cannot measure the anguish these roles cause.

To be clear: For Bambara, the issue is not masculinity or femininity, but our relation to these nodes of being as trite, violent roles we are called to play. Our relation to “roles,” she argues, should be the following: “to submerge all breezy definitions of manhood/womanhood (or reject them out of hand if you’re not squeamish about being called ‘neuter’) until realistic definitions emerge through a commitment to Blackhood.” This work will not happen overnight and must begin with the self, for there “ain’t no such animal as an instant guerrilla.”

If we are to make it on the other end of these perverse ways of relating, “family” or intramural connection cannot revolve around “a socially ordained nuclear unit to perpetuate the species or legitimize sexuality, but [be] an extended kinship of cellmates and neighbors linked in the business of actualizing a vision of a liberated society.” We’d fare better if we cherish and nurture the love and connection we experience that isn’t from our “parents” or “siblings; the love we experience that isn’t romantic. These types of love and connection are not inferior. They eternally stand against the sources of our suffering.