From the moment President Biden announced he would keep his campaign promise to appoint a Black woman to the highest court in the nation if given the chance, questions of whether a Black woman could qualify for the role swirled around the nomination. Following a contentious confirmation process, Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson was voted into the Supreme Court by the Senate. Each time, Jackson noted that she was proud to carry on the legacy of Black women to the highest court.

“I proudly stand on Judge Motley’s shoulders,” Jackson said in February, during her confirmation hearing. She called Motley’s life and career “a true inspiration to me as I have pursued this professional path.”

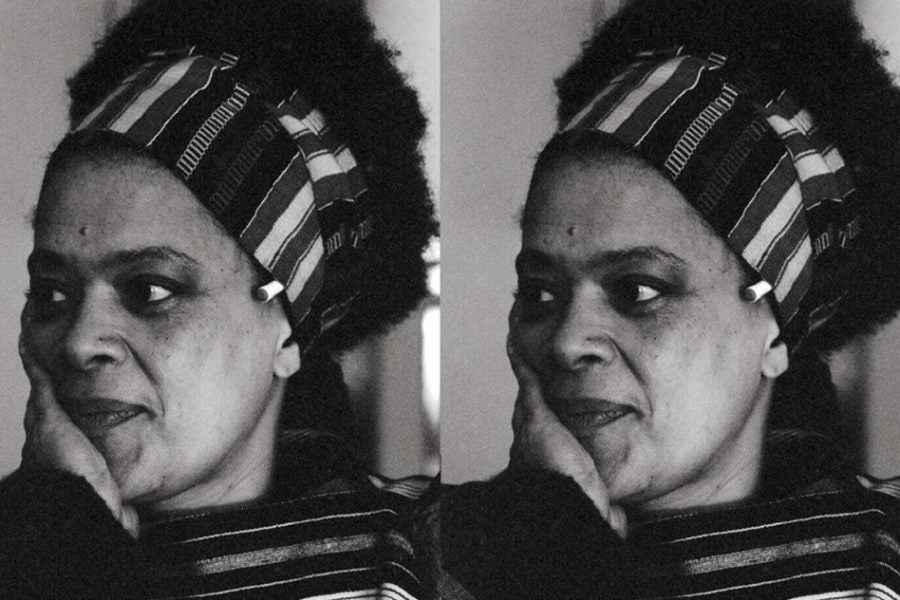

Today, as Justice Jackson joins the bench, we celebrate her hero, Constance Baker Motley, who paved the way for the historic moment.

Born in New Haven, Connecticut in 1921 to immigrant parents from Nevis, Motley was the ninth child out of 12. Before migrating to the United States, Baker’s mother Rachel Huggins was a seamstress and a teacher, while her father McCullough Alva Baker was a cobbler. However, once in America, her mother became a domestic worker and her father, a chef at Yale University.

Her mother later became a community activist and founded the New Haven NAACP chapter. While in high school, Motley served as the president of the New Haven NAACP youth council.

Though she graduated from high school with honors in 1939, prospects for attending college were slim as her family couldn’t afford the tuition. However, she had impressed a local white businessman, who had heard her speak at a community center, and he offered to fund her education. Baker would attend the historically Black college Fisk University for only a year before transferring from the southern school to New York University.

Following her graduation in 1943, with a degree in economics, Baker enrolled in Columbia Law School.

During her second year at Columbia Law, she was hired by Thurgood Marshall—before he was appointed at the first Black Supreme Court Justice—as a law clerk for the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund (LDF). According to Motley’s autobiography Marshall “had no issue with her being a woman.”

After graduating in 1946, the LDF hired her as a civil rights lawyer, making her the fund’s first woman attorney. She was the lead trial attorney in cases that represented Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the Freedom Riders, and the Birmingham Children Marchers.

From 1945 to 1964, she was one of the lead strategists for most of the major Southern civil rights protests. Motley’s work within the Civil Rights movement resulted in many death threats. Armed men guarded her home while she slept. She dealt with harassment from law enforcement while her friend Medgar Evers transported her back and forth to court. She narrowly escaped death, as Evers was murdered shortly after she left the state of Mississippi.

While with the NAACP, she wrote the initial complaint for Brown v. Board of Education. The landmark case fought to desegregate schools. At the time of the case Motley was pregnant with her first and only child for her husband Joe Motley. In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court found segregated schools unconstitutional in 1954. The ruling was met with much violent resistance from white southerners and it would be years before school systems would comply.

Motley successfully argued 10 Supreme Court cases and won nine. The tenth, regarding jury composition, would later be overturned in her favor. She also assisted in nearly 60 cases that reached the high court.

Motley’s biography “Civil Rights Queen: Constance Baker and the Struggle for Equality” detailed the misogyny and racism she experienced throughout her career. She was told that she and other African-Americans didn’t belong in the courtroom. She was rarely if ever properly addressed in the courtroom and was only addressed indirectly as “her” or “she.”

In her autobiography, Motley said she never was discouraged by doubts concerning her background. “I was the kind of person who would not be put down,” Motley wrote. “I rejected any notion that my race or sex would bar my success in life.”

Race would continue to be an obstacle for Motley. In 1966 when she was nominated by President Lyndon B. Johnson to the federal district court, her appointment was delayed by Mississippi Senator James Eastland. Eastland, a white supremacist compared her her civil rights advocacy to communism. New York Senator Robert Kennedy blocked Motley’s nomination to the Court of Appeals citing it would be “too political” appointing two Black NAACP lawyers to federal positions. The role was previously held by her mentor, Justice Marshall.

Motley was eventually confirmed by the Senate and became the first African-American woman federal judge. She presided over landmark cases for women’s rights and racial discrimination. She served as Chief Judge from 1986 until her death in 2005 to congestive heart failure.

Motley’s work left a legacy of endless possibilities for Black women litigators. Earlier this year, the Pew Research Center released a report stating only 2 percent of those who ever served as federal judges in the country have been Black women.

President Biden has nominated 13 Black women to be circuit court judges, eight of whom have been confirmed, since taking office.