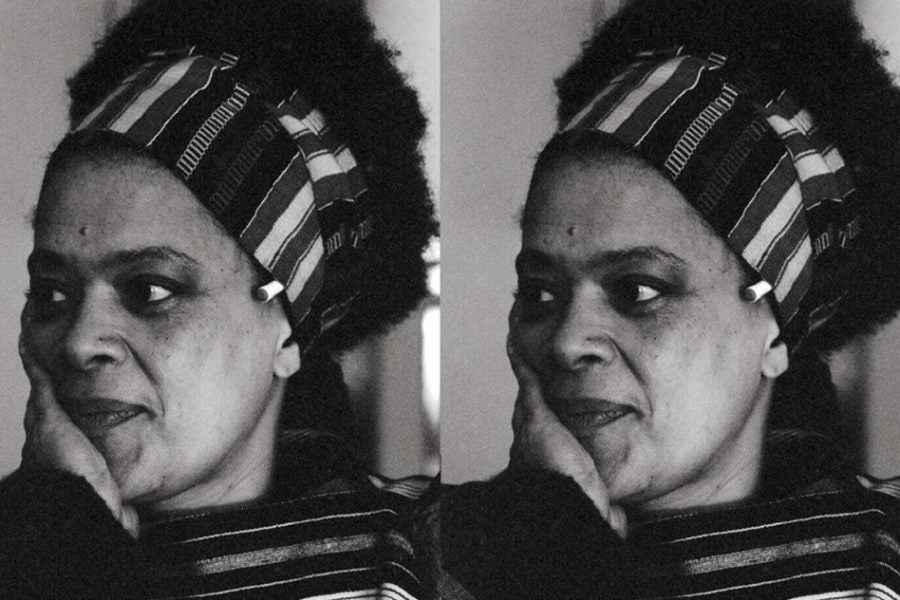

By talking with the chiefs who live among us, ESSENCE CEO Caroline Wanga explores Black women as chief executive officers of home, culture and community.

The leading cause of bankruptcy in the U.S. is medical debt, which means that the state of your health determines the stature of your wealth. It’s why Dr. Margaret-Mary Wilson, is leading the charge to support our health needs and strengthen our wellness narrative.

As Chief Medical Officer and Executive Vice President of America’s largest health insurer, UnitedHealth Group, Wilson is focused on building health equity through clinical innovation—including expanding access to care, lowering costs, improving outcomes, and encouraging patient self-advocacy. She joined the UHG organization in 2008; but long before she became a top executive at the insurance giant, Wilson dreamed of becoming a doctor back in her native Nigeria. Her ambition was met with “it’s not a profession for girls” opposition, yet Wilson persisted, enrolling in medical school at 16 years old and graduating by age 21.

Here, she shares lessons in leadership, the global community, and what she’s learned about creating an impact.

Caroline Wanga: Who is Dr. Margaret-Mary Wilson?

Margaret-Mary Wilson: I’m Victoria’s daughter. I will never let myself forget that. Victoria was my mother; she died two years ago. She was a single, divorced mother—my father had walked out on her. She couldn’t read or write. She struggled financially, and she was poor after my father left. But the one thing she knew was that she wasn’t going to let me walk her path. And that’s who I am at the core. My mother put me through medical school, and I became a doctor in Nigeria. It was a hard life. Doctors weren’t paid much, and I didn’t have a lot of money. But that started my search for answers. Something happens when, as a young doctor in your 20s, babies are dying, and mothers are dying. It pushed me to search for more. And I owe my journey in medicine to that.

WANGA: How does a young person whose mother did everything she could to provide for her—but probably always felt like there wasn’t enough to do it all—become a young person who believes she can be a doctor?

WILSON: Quite frankly I didn’t always believe I could be a doctor. One of my uncles asked me what I wanted to be, and at the time it sounded like a good thing to say. I was 7 years old and said, “A doctor.” But he then said to me, “Oh, you can’t do that. It’s not a profession for girls.” And at that point, I didn’t know what it would take, but I was determined to prove him wrong. You throw in a bit of grit and determination and step by step, you get there.

WANGA: How did you go through the process of becoming a doctor as a Black woman, in a field that doesn’t have that much texture of identities and representation?

WILSON: Well, first, I went to medical school in Nigeria—so we were all Black, so that took care of that part of things. But we were a class of about 200, and only 30 of us were women, so it was a hard walk. What it did show me, however, was that medicine is not impossible for women, because there was nothing gender specific about it. I was determined to do something—I didn’t know what—to increase gender diversity. And it’s fortunate that decades -later, I work with an enterprise that’s doing just that. Just months ago, UnitedHealth Group committed $100 million to advance diversity and equity in the clinical workforce over the next 10 years.

WANGA: Why would a company of that size and scale -decide that a $100 million commitment is a way to help—to make sure that the way that health care is provided is really working for all? Because many of us, as Black people, have had issues getting through the health-care system—finding care, getting good care, having coverage, having our doctor not care enough because we’re Black, and everything in between. How does the $100 million change that story?

WILSON: It changes the story fundamentally because most people are like me. I’m Black, an African -immigrant, a lesbian, and a legally married woman living in the state of Texas. And when my wife and I moved to Texas from New York, we needed a doctor. Who did we look for? A doctor who got us. A doctor who looked like us. A doctor who represented us in one way or another. The people we serve as clinicians, need to look like them. It saves lives. So when you see United committing to that amount, it’s because we recognize that if we change the health-care system, if we’re going to transform health care, then it must be equitable, and the workforce must be diverse. If you look across America today, a Black woman who goes in to have a baby is about 3 times more likely to die than a Hispanic or White woman. Those are the glaring statistics.

WANGA: How should we navigate the healthcare system?

WILSON: I’m sure you could tell me what was in your bank account to the last cent. But I bet very few people could tell me what their blood pressure was this morning. When we think about wealth and we think about power, let’s not forget health. Even though I don’t have a lot of hair, one thing I’m really picky about is my haircut. I’m not going to let my barber get it wrong. I will also empower myself when it comes to my health.