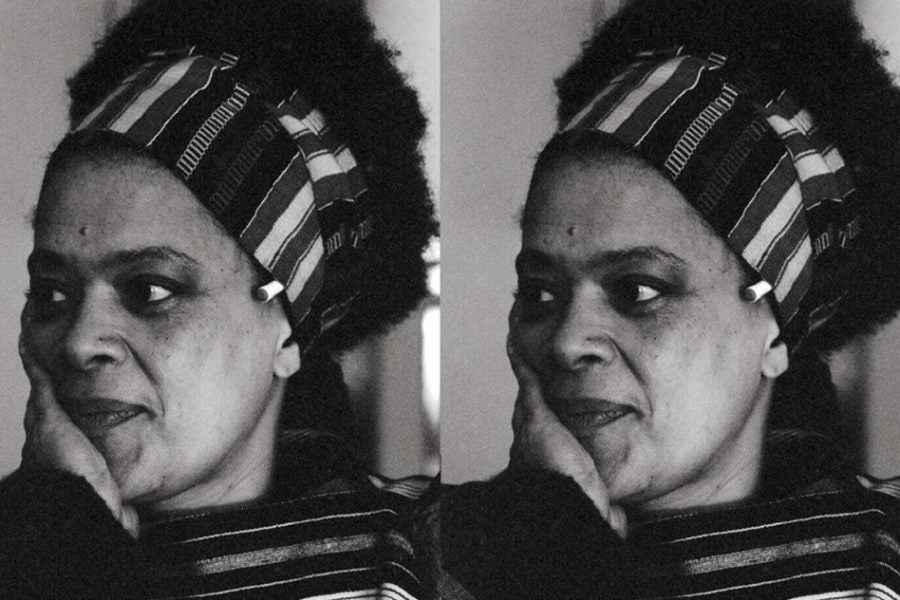

On the morning of July 8, Janice Tappin-Miller is warm, but the undercurrent of grief is strong. As she welcomes me into her home in Waxahachie, Texas, I pass the dining room. It’s filled with photos of Arlana Miller, Janice’s late daughter. “I really miss my baby,” Janice tells ESSENCE. “That was my baby.”

Arlana, who died by suicide this past spring, began her first year at Baton Rouge’s Southern University and A&M in the fall of 2021. She was a skilled cheerleader majoring in Agriculture, Family and Consumer Sciences. Southern awarded her the David Scott/JAG STARS scholarship—a full ride. She chose the major because she was looking to become a psychiatrist and wanted to help others.

“She never made you feel alone,” says Mya Mingo, one of Arlana’s cheer mates at Southern. “After practice, everyone would be gone; me and her would still be in the parking lot, talking and talking. She knew how to encourage, just lift people’s spirits up.”

On May 4, days before her summer break began, the 19-year-old posted a since-removed suicide note to Instagram. She detailed her ongoing struggle with mental health and the impact contracting COVID-19 and tearing her anterior cruciate ligament had on her. “Once she got the injury, it felt like things took a turn,” says Floyd Sias, Southern University’s head cheerleading coach. “I think she felt like she didn’t have a place anymore because she was hurt and she couldn’t try out [for the next year]. But we had a conversation. I had assured her that she was fine, that she had a place on the team. I could tell that was really getting her down.”

Arlana also voiced concern about her grades, in her public letter and during a conversation with her mother on the day of her passing. She texted her mom that she was failing a math class, which prompted a phone call from Janice. ”I said, ‘It’s okay, baby. Just drop the class.’”

Arlana then revealed she was taking six classes, two more than she had during the first half of the year. It was too late in the semester to let go of any.

“She got quiet on the phone,” Janice says about their final call. “I believe she had a moment where she just thought she was going to fail us, but she could never fail me.”

“She was a great person. I feel like the world needs more people like Arlana.”

––

Arlana Janell Miller was born in 2002 to Janice, an educator, and Pastor Arthur Miller II. She began dancing at age three when her mother enrolled her in dance classes. By the first grade, Arlana was cheering, too. She was a straight A-student, shy yet bubbly when you got to know her and frequently received awards at the end of each academic year.

The family, which includes Arlana’s older brother, Raylon, relocated to Texas when Janice took a teaching position in 2016. (The relocation did not have Arthur, as the couple divorced in 2010.) Arlana was the new girl at A.W. Brown Leadership Academy, a K-8 school in Dallas. She made the cheerleading team and fit right in.

“She went to A.W. Brown and didn’t hardly know anybody. Then she made cheer there, ran for homecoming court and was first-runner up,” Janice says.

Cheerleading was the teen’s joy. She ran track as well and was talented, but in middle school decided to stop splitting her time between multiple physical undertakings. At the start of her senior year at DeSoto High School, she was rewarded for focusing on one sport.

“I always hinted at her like, ‘Girl, I think you’re going to be cheer captain,’” says Whitney Walton, one of Arlana’s closest friends. Walton’s gut feeling proved to be right. During one of the 2019 home games, the team took a break; moments later, the cheer coach came out with a sash for Arlana that read ‘cheer captain.’ Janice smiles as she retells the story, recalling her daughter’s tears, gratitude and shock. “They filmed it and everything, and she was crying. I was crying.” It was a dream come true.

Now, Janice has a new outlook on her daughter’s relationship with the sport, saying it helped her cope. “It was her way to not be by herself, to be doing something and not in her dorm room. I learned through my grief counselor, people who are sometimes depressed, they deal with their depression by helping other people or doing things for other people.”

The appointment as captain came a few months after an event that rocked Arlana—the death of her maternal grandfather, John Tappin Sr. The two were inseparable during his life. “Her Pawpaw was like her dad. That was her everything,” Janice says. Arlana would spend time in Louisiana with him, along with her cousins, riding four-wheelers and horses. John Tappin III, Arlana’s first cousin and the son of Janice’s twin brother, reminisced on the relationship between Arlana and her grandfather. “They were a match made in heaven, literally,” he says. “If they could hold hands every day, they would.”

After her daughter’s death, Janice also contemplated how Arlana may have felt after her grandfather’s passing.

“I wonder, did she ever really grieve her Pawpaw dying?”

––

The COVID-19 pandemic, which began towards the end of Arlana’s junior year of high school, profoundly impacted young people’s mental health. The isolation, and witnessing mass sickness and death, was a lot to bear. In 2022, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported more than 25% of teens struggle with mental health. In 2020, the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (leaning on CDC data) also shared that in Louisiana, suicide is the third-leading cause of death for those between the ages of 10 and 24.

Black women and girls still don’t feel comfortable fully opening up about their trials, even though they’ve been feeling the weight of the past 2.5 years—and beyond.

“Intergenerational transmission of trauma and ideologies is prevalent among African-American families and contributes to cultural norms across the diaspora,” Xonjenese Jacobs, Associate Director of Program Performance for Pace Center for Girls, an advocacy program, writes ESSENCE in an email. “For Black girls, there is an added layer to include the standards by which they are expected to behave and how they are perceived in society. Each of these interpersonal level interactions have an influence on the experience of Black girls and their mental health outcomes.”

Jacobs also writes that girls make up a large percentage of the mental health-related emergency room visits that have taken place since the pandemic started.

––

“She walked in the Mississippi River,” Janice painfully explains. Captain Keith Kibby, the Baton Rouge sheriff who found Arlana’s body, told her mother that if they had arrived two or three minutes earlier, they might have been able to save her.

“All I remember is just screaming and hollering until I just couldn’t breathe anymore. I felt like somebody took the air out of my chest,” she says of the night of Arlana’s death. She fell asleep in her daughter’s room, aching to hold her once more.

Tears roll down Janice’s face as she gives me the details of a previous grief counseling session. She told the therapist, “I’ll never get to see her graduate from college. I’ll never get to see her get married. I’ll never get to see her have any kids.”

I cry, too.

––

“I want people to know she was the best person ever,” says Denim Hill, one of Arlana’s childhood friends and fellow Southern Jaguar. “I ain’t never had that type of bond.”

A cheer mate, Jada Taylor, shares a similar thought.

“She was a great person. I feel like the world needs more people like Arlana.”

Since Arlana’s passing, Southern has launched the Arlana J. Miller Memorial Scholarship Fund, a monetary award that will benefit two cheerleaders. It’s in line with Arlana’s compassion: in 2020 she began her own scholarship that high school seniors would be eligible for. Janice is now maintaining it in her daughter’s stead, telling ESSENCE this year’s bursary will go towards a Louisiana State University freshman.

A non-profit organization, the Arlana Janell Miller ‘Check on Your Strong Friends’ Foundation, is also in the works. “We just want to help anyone we can. We’re just teaching strategies with dealing with anxiety, depression, stress, Janice says. “I didn’t realize so many people were going through depression.”

The community has been there in the wake of the tragedy. For weeks after Arlana’s passing, neighbors cooked and sent flowers to the family. Another had customized ‘Mom’ cookies made. Arlana died the Wednesday before Mother’s Day.

Towards the end of the afternoon, she walks me to Arlana’s pristine bedroom. On the wall, there are photos of the young woman. I also see a blanket with a portrait of her on it. Her mother hasn’t fully sorted through her belongings yet.

“Sometimes I don’t come in here and sometimes I do. I just wish she was in here,” she says.

If you or someone you know is in crisis, please call 988 to reach the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. You can also call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255, text HOME to 741741 or visit SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources for additional resources.