The forecast for this summer is sure to be a scorcher with the assistance of this generation’s most impactful seven Black women artists. Curated by icons Racquel Chevremont and Mickalene Thomas, the Set It Off exhibit will do just that in the art world. With over 50 works between the curators, Leilah Babirye, Torkwase Dyson, February James, Kameelah Janan Rasheed, and Karyn Olivier—Set It Off expands the lens of Black women’s artistry, producing a meaningful event you can’t miss. ESSENCE caught up with featured artists Leilah Babirye and February James over Zoom and waxed poetic about being hand-selected by Mickalene Thomas and Racquel Chevremont, creating during a pandemic, and the way mediums find the artist and not the other way around.

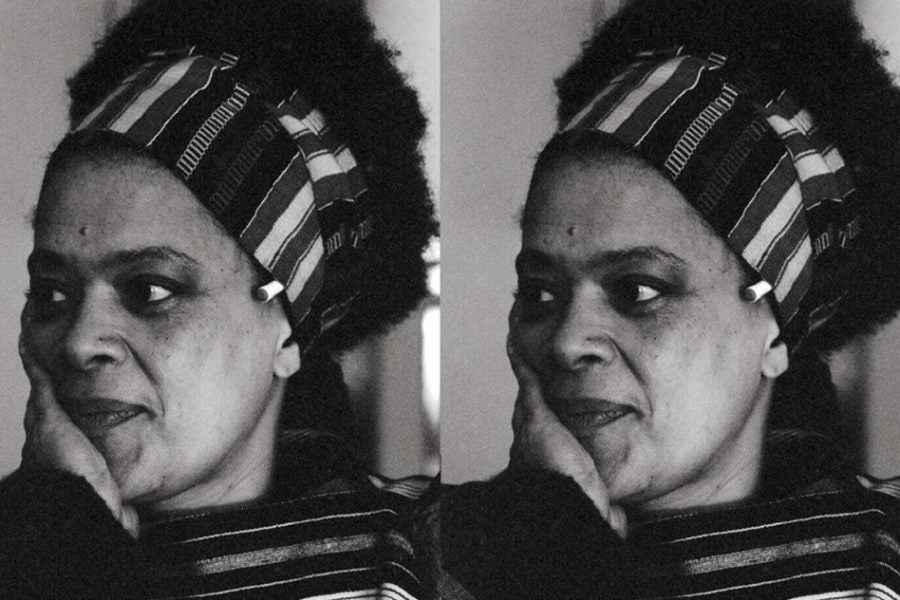

Based on her gritty, massive sculptors (literally as tall as 15 feet), composed of debris collected from the streets of New York with elements of ceramics, metal, and wood that has been carved, welded, burned, and glazed, viewers would never expect Ugandan-born artist, Leilah Babirye to the be laid-back, but sort of bashful, kind-hearted spirit she displayed over Zoom. She is at a desk in the middle of her Brooklyn studio under fluorescent lights with her materials around her when she says her creative process is about being in the right mood. “I never stress myself. I’m into work for three-four hours, and I’m out. I can’t exceed that,” Babirye said.

The short work schedule shouldn’t be mistaken for laziness. It’s instinct. The same instinct that tells her when an art piece is complete. She admits to sitting on several incomplete pieces as long as four years old. Even when gallerists and collectors push, if Babirye doesn’t feel it, she won’t budge. She told a collector who was pining over a piece, “I don’t feel you having it.”

Those same instincts guided her through the quarantine. The pandemic was a mixed bag of either success and exploration or failure and heartbreak. For Babirye, it was the former. Babirye saw a breakthrough in her career at the peak of the pandemic. “I thank God that people still had money to buy art during a global pandemic.” Living only 15 minutes away from her studio, she produced and sold a lot of artwork and took care of almost 17 families back home in Uganda. Yes, 17 families.

A mighty enormous payoff for someone whose creative endeavors only began from a pass/fail art course she enrolled in on the fly because it was impossible to fail. As one would imagine, support for a future in the arts for the daughter of African parents with careers in accounting and business was unlikely. Babirye’s father refused to pay tuition for an Arts degree and insisted on law school. As luck would have it, on a visit to the law school where Babirye was expected to attend, students had lunch on the neighboring campus: an art school. There, she met an art professor carving into a tree trunk. Babirye’s mind was made.

Her decision cost her a year off, as her father refused to help pay the cost. Eventually, he caved. While in school, Babirye sold her first work for a million Ugandan shillings (roughly $500) made from literal garbage. Blown away by the payout, Babirye’s father began gathering trash in support of his daughter’s work. Later, however, Babirye’s publicized woman-loving-woman lifestyle was too much for her Muslim clergy father to bare, fracturing their relationship completely. She told ESSENCE that while her father always knew she was gay, coming out crossed the line.

By nature, her sculptures are transformative. Initially, her choice to use trash materials reflects her advocacy for the LGBTQ+ community. Ugandans use the term “ebisiyaga”—sugarcane husk—to refer to queer folks as waste. “Not even insects can eat sugarcane husk because there’s nothing left in it, and that is how gay people are being called.”

Since then, Babirye says her work and materials have matured, even though the message is the same. The mediums vary from sculpting with miscellaneous scraps, to painting, to wielding, and ceramics. She finds a lot of strength when working with those materials. “I’m grounded when I’m doing my ceramics, because that’s the only time that I can stop. With sculpture, wood, and paint, I can work till I feel I can’t do it,” she says. “But with ceramics, it tells you, ‘Stop, you can’t exceed a certain height.’ It will collapse.”

Currently, she wields and then bronze is next on her list.

“I want to give people a headache,” she says. “I want to blow them away, when they stand around my work,” she says. “I worry my pieces are getting smaller, so I want to give them a headache.”

The pandemic was a bit different for D.C. native, February James because unlike Babirye, she is a parent. Between the fear of coronavirus, the racial uprising of 2022, and her son’s transition to online learning, James’ work dynamic drastically changed. “Immediately, my resolve with my studio life, my personal life is always: there’s no one in the room more important than my son, and his feelings come first,” she says. “So I close the doors and I don’t even have a studio. I’m with my son.” But while she wasn’t painting, she did pick up pottery with her son, noting that he is an amazing sculptor in his own right. Though sculpting became a hobby that grounded her, she has no intentions of sharing or selling those works she created.

Sculpting also helped James share creative space with her son. She gushed over his talent, not as an adoring parent, but in community with a fellow creative. She explains that because he isn’t burdened with knowledge, his fearlessness reminds her to be lighter and confront her imposter syndrome. His influence is clear as there is a series of paintings within Set It Off’s multi-part installation, These Are My Ghosts To Sit With called And Then The Spirits Came To Me With The Burden of Truth. “Some of the work that I do is so heavy with emotion, and I don’t intend to make it heavy for the viewer. He helps me to invite this element of play back into the work because that is life: work hard, play hard. You have to have balance somewhere.” The duality of her personal balance appeared again as she describes her workspace as choreographed chaos with materials all over–which is completely different from her homelife, where everything is in order.

James calls watercolors her pacifier. It’s an inexpensive material she’s utilized since childhood. The marriage between her use of watercolors, ink, pastels and oils has resulted in ethereal realms that lingers with audiences. For Set It Off James produced 28 works, specifically for the exhibit. While she is tight-lipped about when and how long her process is when commissioned for a showcase, she does open up about her feelings after the work is done. Like many creators, James admits she used to struggle with seeing her work once it was available to the public, because she would start to mentally modify it. “It used to be hard. I would still be editing and it would rob me of the moment of the show.” Now, she’s better at accepting the work as being done. “I decided that when the work leaves, whatever’s supposed to be there, is there. Everything that was not there was for the next go round.”

These days, James enjoys watching audiences experience her work, seizing the opportunity to engage with her audience at shows. Knowing that sometimes her work can be a little coded, she makes herself available to be in conversation with them too. However, she won’t be caught explaining too much. The unspoken-but-all-knowing cultural ‘head nods’ to Black audiences often appear in the artwork’s titles. For example, Auntie’s New Friend, Chicken wings and mumbo sauce and GodFather of Go-Go (Chuck, Baby) and most recently, Tell Them I Said NO.

James maneuvers through the art world’s pervasive elite white gaze with ease. So while her work is described as investigating the complexities of the Black identity, for James the investigators are Black; the investigation is for us, by us. She is intentional about gatekeeping, warding off outsiders. “If you know, you know. And if you don’t, you don’t. You can do your own research and look it up and become informed yourself. Because if you don’t get it, maybe it’s not for you.”

James takes the responsibility of being hand selected by Mickalene Thomas and Racquel Chevremont seriously. For a moment she gets emotional about the space carved out for her specifically to be included in the exhibit. Chevremont and Thomas’ appreciation of her talent paired with the encouragement to continue to be her raw self carried her through the creative process. “Just having that allowance and freedom coming from two people that I respect so greatly in this business meant a lot to me,” she says. “I thought about them before I thought about any collector or viewer seeing the work. It was a conversation I had with them when I was invited to the show that I took with me every day in the studio. They were the fuel to make and do better and greater.”

The Exhibit will run from May 22 – July 24, 2022.