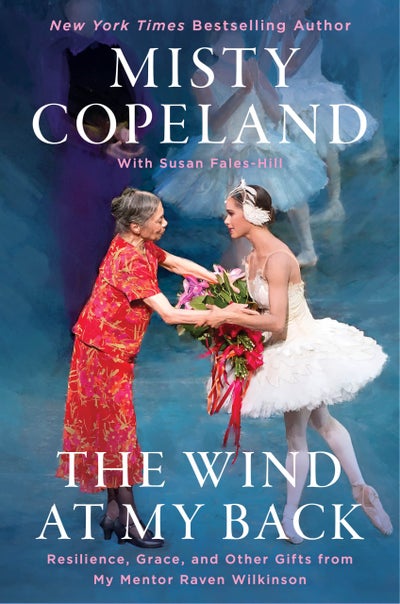

The following passage is excerpted from the book THE WIND AT MY BACK: Resilience, Grace, and Other Gifts from My Mentor, Raven Wilkinson by Misty Copeland with Susan Fales-Hill. Copyright © 2022 by Misty Copeland. Reprinted with permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

Raven seamlessly helped bridge the gap for me between Misty the person and Misty the ballerina. As a dancer I’ve always felt right at home on the stage. There’s a sense of safety I feel hav‑ ing complete control over the choices I make and the freedom I feel during a performance that I didn’t always possess when I stepped off the stage. Growing up insecure and ashamed that we lived in a motel and were on food stamps, it was often hard for me to connect with people, especially people who I felt judged me or made me feel different. But Raven was that missing piece that helped me to connect the power I felt onstage to the power I held off it. She did this in the most beautiful and clear way that, for me, as a visual learner, made complete sense. She led by example. She was free of judgment, patient and warm. Raven’s mastery lay in her ability to give of herself through her loving actions and words. It was as if Raven was determined to pour all the energy that she could no longer expend on her own perform‑ ing career into helping me with mine.

Early one morning I’d walked my usual seven‑block route to the Met from home for company ballet class. This particular morning, as I stood on the corner of Amsterdam Avenue and Sixty‑Fifth Street, waiting for the light to change, I noticed the groups of teenagers as they entered the big glass doors of LaGuardia High School, the elite performing arts public high school steps away from Lincoln Center. There were budding musicians holding instrument cases, aspiring artists with portfolios tucked under their arms, and clusters of “bunheads,” with erect posture and turned‑out feet. It was always inspiring to see a new generation of young dreamers. As I watched them, I hoped to one day be the sort of mentor Raven was becoming for me. I was only beginning to understand the vital importance of someone like her in an artist’s life.

The light changed, and I ran across the street and entered the parking garage that led to the Metropolitan Opera House stage door. I checked in at the security desk with my personal ID card, the same one I’d had since I was nineteen years old. The picture was unchanged, and the ABT logo had almost completely faded away. I opened the door that led backstage and stopped at the podium that holds the daily sign‑in sheet to write my initials before walking down the long corridor leading to the dressing rooms and the stage. The fluorescent lights overhead flickered, and my heels clicked on the scuffed linoleum floors as I passed the familiar row of lockers used by the Met orchestra. This was the most unglamorous part of this majestic opera house. But after ten years, I felt a pride and a comfort in walking this hall as an insider and veteran.

I paused to look at the announcement boards opposite the lockers. One featured the daily rehearsal schedule. Next to it was a board with the weekly casting, as we alternated ballets once a week. The title read “Casting: Princess Florine.” This is a significant role danced by both principals and soloists in Sleeping Beauty, which, next to Swan Lake, is one of the most iconic classical ballets choreographed by the legendary Marius Petipa, the godfather of epic story ballets, and set to the music of Tchaikovsky. My eyes traveled down the list of names. As I reached the bottom, my heart sank.

Seven women were cast in the role, some of them still members of the corps de ballet. All the female soloists had been cast . . . except me. By then I’d been a soloist for four years. I’d gotten great reviews so far that season and had danced roles comparable to Princess Florine in other ballets. I’d given everything I knew how to give. Kevin, the rest of the artistic staff, and the choreographers had given me such great feedback about my performances. Alexei Ratmansky told me I was the best Milk‑ maid he’d ever cast in The Bright Stream.

But most importantly, Raven, who’d danced with some of the “greatest of all time,” had gushed over my performances. She was my biggest fan and extremely complimentary of my acting and character portrayal. Yet I seemed to be standing still within ABT. I certainly was not getting any closer to my ultimate dream: making it to principal dancer. At that moment, I remembered what Raven had told me just days before. In her soft, yet strong voice, she insisted that no matter how hard the road got, no matter how much it seemed that a career as a classical bal‑ erina would not happen for her, no matter how many times she was told “no” or “it’s not possible,” she pushed through the adversity on the strength of having hope and faith that with hard work, all things are possible.

The company’s casting decisions are cloaked in a kind of mystery that surrounds the choosing of a pope. Kevin and his second‑in‑command at the time, Victor Barbee, usually made the casting choices in consultation with the ballet coaches. But Kevin, as artistic director, has the final say. It is a very personal decision. But when an outside choreographer comes in to create a new work, they might see something in you and request you. And this almost always happened with me.

When it came to the full‑length classical ballets that were in ABT’s repertoire, there were no auditions for roles. You had to be picked. Once again, when it came to a pure classical role, I had not been chosen. This action spoke more loudly than any praise the artistic leadership team had given me. As I walked down the long hallway, my thoughts raced back to the budding artists from LaGuardia. I wanted to be able to tell them, like Raven told me, “All things are possible with hard work.” But would I be lying? Was I lying to myself? Would any Black ballerina ever shatter ABT’s glass ceiling?

That’s the emotional space I was in as I reached the end of the hallway. I stopped just before the artistic staff’s offices to collect myself; then I rounded the corner, entering the next hallway that led right to the dressing rooms. I needed to switch off the negative thoughts because thinking this way wouldn’t enhance my dancing. Like many dancers of color before me, I had to tune out my pain and fear and tuck it away in order to perform at my best. Over time, the constant need to compartmentalize chips away at your spirit and drains your energy. I took a few deep breaths, swallowed my disappointment and frustration, and headed to the dressing room to get ready for company class.

That night I called Raven. “Hello,” she answered. Just hearing her warm, rich voice soothed me.

“Raven, it’s Misty.”

“How are you?” she asked. I could hear the joy in her voice and hesitated for a moment to share my bad news. “Misty?” she prompted, the tone in her voice indicating she sensed a problem.

“I’m not doing so well,” I admitted. “Tell me everything,” she insisted.

And so, I did. I explained it all and shared my complete discouragement.

“Well, that is very disappointing,” she responded calmly, “and it’s not right.” Just this affirmation from an artist of her stature, a ballerina who knew and had suffered more than I could imagine, was a relief.

“I think you need to go and speak to Kevin,” she advised.

I froze in fear. “I don’t know if I can do that,” I stammered. “Why not?” Raven asked gently.

“Because . . . I . . . I’ve never asked him for a role.”

Without hesitation, she enlightened me. “I’m certain others have.” Raven spoke firmly from her personal experiences with backstage politics in the ballet world. “What do you have to lose?” she asked simply. I had no answer.

Although Kevin was, at his core, a benevolent man, as dancers, we all lived in fear of the power he held over our careers. And ABT, like every other ballet company, was not a democracy. Many of us, including me, didn’t challenge decisions made by our artistic leadership. We accepted them and walked to our marks.

“It’s not disrespectful to go to your artistic director and let him know what your aspirations are and ask him why you weren’t cast when you have danced roles that prove you are up to this one,” Raven explained matter‑of‑factly. As gentle and kind as she was, there were moments when Raven revealed the steeliness that had made her journey possible. This was one of them. Her definitive tone indicated to me that the time for action had come. I knew she was right.

“You sound like Olu; he used to say things like that to me,” I confessed.

“I knew I liked him. He’s a very wise young man. You should listen to both of us,” she teased. “Don’t be afraid,” she added. “Remember, when you go speak to Kevin, I’ll be the wind at your back.” And I knew she would be.

After we hung up, I thought about Raven at nineteen, auditioning for the all‑white Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo in 1955. She had studied at the prestigious Swoboda School, under Maria Swoboda herself, since the age of nine. The Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo had just taken over the school. Though Raven had been a standout student, one of Madame Swoboda’s favorites, she’d auditioned twice for the company and been rejected. She was going in for a third time when another dancer warned her, “You really shouldn’t. They can’t take you. They tour in the South. You’re Colored. It’s never going to happen.” Raven knew the fellow dancer was offering this advice out of concern, not competitive spirit. She appreciated his wanting to protect her, but she was not ready to give up on her dream. She’d enrolled at Columbia University, in the tradition of her educated family, but her heart was at the ballet studio. “The least I could do was try,” Raven thought.1 And so she did. The Wilkinsons were strivers, not quitters.

On the appointed day, she went to the rehearsal studio on West Fifty‑Seventh Street, where the school and company were located. She was auditioning for the head of the company, Sergei Denham himself. Mr. Denham was a Russian‑born banker who had fled the Communist Revolution. Like Raven, he’d fallen in love with ballet as a child, when he saw the Imperial Ballet perform. In 1945, he’d taken over leadership of this company, which was an offshoot of the original Ballet Russe founded by former members of Sergei Diaghilev’s company.

A distinguished man who always wore custom‑made suits, Denham sat in his folding chair waiting for the dancers to begin. After watching them take ballet class—a class led by none other than Freddie Franklin2—for an hour and a half, he asked to see the dancers one by one. Raven was up. In his thick Russian accent, he asked, “Darling, how would you like to join the Bal‑ let Russe de Monte Carlo?” Raven nearly fell over and accepted joyfully.

He warned her that there could be problems when the company toured in the South, where segregation was still the law of the land. She insisted she could handle the challenge.

“You’re not very dark,” he commented. “If you took a Russian name, we wouldn’t have to admit that you are Colored.”

As many who were fortunate to get to know Raven came to understand, Raven never denied being a Black woman, even if it meant costing her the opportunity to dance. “Mr. Denham, I can’t deny what I am. How can I dance with my whole self if I do?” she asked him.

“Fair enough,” he said. “But don’t advertise it.”