There wasn’t much coverage of a report issued last month by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. But the information in it would have hit home for many Black women who work in the child care industry and are making the incredibly difficult decision to leave the profession they love.

The bank’s report used data to illustrate how COVID has disproportionately reduced retention and increased turnover for Black child care and early education professionals. These findings, as well as data published by other entities, have highlighted the harms of the broad approach our nation has typically taken to improve the child care system. For Black early care and education professionals and advocates like me, these findings offer a confirmation of what many of us have always known and what COVID worsened: we are experiencing vastly different systems, resource access, and outcomes.

My father, to this day, always says, “If you tell me the truth, I can help you out of any situation. But if you leave out the parts you don’t like, I can’t help you. If I don’t know everything, I can’t fix anything.”

Most people will acknowledge that child care work is extremely undervalued and shamefully underpaid. What’s often left out is the fact that this work is devalued because the history of the profession is rooted in enslaved Black women caring for white children. Although chattel slavery ended, the diminished position of Black women in this profession was never addressed despite the central role Black women continue to play in the child care field.

We know that our continued recovery from COVID and fixing the broken child care system will require significant federal investments to increase pay, advance to higher positions, access health benefits, and other resources to support a stronger workforce. But money alone won’t fix some of the system’s deepest problems.

Beside sustained robust funding, policies must actively dismantle the foundations of racism and anti-Blackness by abandoning the “high tide lifts all boats” approach that only exacerbates existing disparities.

Policy must address the clear inequities and harms experienced by Black child care professionals and the children and families they serve. The intersecting racial, gender, and economic inequities endured by Black women aren’t just a consequence of deliberate laws and policies over many generations, but of our unwillingness to thoroughly disconnect our current systems from the roots of that history.

If we want to confront this head on, we need the same intention to undo those harms as there was to enforce them. We need a blueprint to begin fully addressing inequities in the child care and early education field. This systemic approach should identify the aspects of American anti-Blackness and racism that were the foundations our present systems and institutions were built on, and through which Black child care and early education professionals have dramatically different experiences, access, and outcomes.

To create an equitable system and undo the harms caused over many generations, policymakers must move beyond broad policy solutions that overlook the hard truths we must face.

The Paycheck Protection Program and Small Business Association loans provided early in the pandemic offer an example of how the inequities of systemic and institutional racism impacted Black child care professionals. These loans could be used to help child care providers remain open or sustain their business and pay employees during COVID shutdowns.

But many child care providers, regardless of race, had significant difficulties accessing these funds. For Black-owned child care businesses, the difficulties were even worse. The pervasive, persistent, and racist inequities within the banking system for Black communities created barriers to establishing the kinds of banking relationships necessary to access those loans, making them virtually inaccessible.

A systemic approach to public policy that centers racial equity includes addressing the intersecting systems that all child care professionals interact with but through which Black child care professionals have dramatically different experiences. Structural and systemic racism changes their access within the profession, whether it’s to maintain their license, secure funds to start up or support their business, gain higher education or training, increase wages, or advance in their careers.

We should also examine broader issues like equitable access to affordable transportation, housing, food, and health care that fall outside the traditional scope of child care policy yet are also rooted in racism and deeply impact both providers and the families they serve.

To create an equitable system and undo the harms caused over many generations, policymakers must move beyond broad policy solutions that overlook the hard truths we must face. Until we do that, we’ll never be able to provide child care professionals with the pay, benefits, dignity, and economic security they deserve.

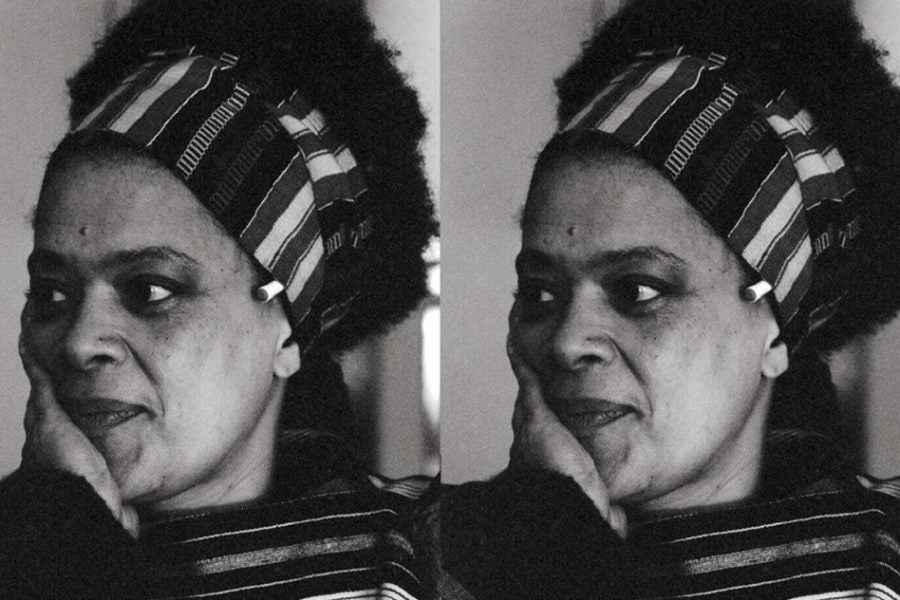

Alycia Hardy is a senior policy analyst at The Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP).